Atlanta's Elite Fashion and Entertainment Consultants

Best dating apps for young people (free app)?

Which makes sense—the less time you spend naked, the less comfortable you are being naked. There is also a relevant study provided by GLSEN Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network that identifies the two biggest reasons for bullying the members of the LGBT community is their appearance and sexual orientations or gender identity. Unless you are exceptionally good-looking, the thing online dating may be best at is sucking up large amounts of time.

T hese should be boom times for sex. Back in 1992, the big University of Chicago survey reported that 20 percent of women in their late 20s had tried anal sex; in 2012, the NSSHB found a rate twice that. The majority of men on Tinder just swipe right on everybody. As of 2014, , the average user logged in 11 times a day.

Encourage them to make new friends and build relationships at school, by participating in after-school sports and clubs, or by joining a religious group that offers clubs or meet-up groups designed specifically for teenagers. Malcolm Harris strikes a similar note in his book, Kids These Days: Human Capital and the Making of Millennials. Pinsof, a founding father of couples therapy, and Arthur Nielsen, a psychiatry professor. Many—or all—of these things dating apps young be true. What if you could teach about love, sex, and marriage before people chose a partner, Pinsof and Nielsen wondered—before they developed bad habits. The 2017 iteration of Match.

6 Dating Apps That Are Putting a Fresh Spin on Finding Love - People now in their early 20s are two and a half times as likely to be abstinent as Gen Xers were at that age; 15 percent report having had no sex since they reached adulthood. Sex may be declining, but most people are still having it—even during an economic recession, most people are employed.

T hese should be boom times for sex. New cases of HIV are at an all-time low. Most women can—at last—get birth control for free, and the morning-after pill without a prescription. If hookups are your thing, Grindr and Tinder offer the prospect of casual sex within the hour. BDSM plays at the local multiplex—but why bother going? Sex is portrayed, often graphically and sometimes gorgeously, on prime-time cable. Sexting is, statistically speaking,. To hear more feature stories, or Polyamory is a household word. Shame-laden terms like perversion have given way to cheerful-sounding ones like kink. With the exception of perhaps incest and bestiality—and of course nonconsensual sex more generally—our culture has never been more tolerant of sex in just about every permutation. But despite all this, American teenagers and young adults are having less sex. To the relief of many parents, educators, and clergy members who care about the health and well-being of young people,. When this decline started, in the 1990s, it was. But now some observers are beginning to wonder whether an unambiguously good thing might have roots in less salubrious developments. Signs are gathering that the delay in teen sex may have been the first indication of a broader withdrawal from physical intimacy that extends well into adulthood. Over the past few years, Jean M. In a series of journal articles and in her latest book, iGen, she notes that than members of the two preceding generations. People now in their early 20s are two and a half times as likely to be abstinent as Gen Xers were at that age; 15 percent report having had no sex since they reached adulthood. Gen Xers and Baby Boomers may also be having less sex today than previous generations did at the same age. From the late 1990s to 2014, Twenge found, drawing on data from the General Social Survey, the average adult went from having sex 62 times a year to 54 times. A given person might not notice this decrease, but nationally, it adds up to a lot of missing sex. Twenge recently took a look at the latest General Social Survey data, from 2016, and told me that in the two years following her study, sexual frequency fell even further. And yet none of the many experts I interviewed for this piece seriously challenged the idea that the average young adult circa 2018 is having less sex than his or her counterparts of decades past. Nor did anyone doubt that this reality is out of step with public perception—most of us still think that other people are having a lot more sex than they actually are. When I called the anthropologist Helen Fisher, who studies love and sex and co-directs Match. For a quarter century, fewer people have been marrying, and those who do have been marrying later. One in three adults in this age range live with their parents, making that the most common living arrangement for the cohort. Over the course of many conversations with sex researchers, psychologists, economists, sociologists, therapists, sex educators, and young adults, I heard many other theories about what I have come to think of as the sex recession. Name a modern blight, and someone, somewhere, is ready to blame it for messing with the modern libido. Some experts I spoke with offered more hopeful explanations for the decline in sex. For example, rates of childhood sexual abuse have decreased in recent decades, and abuse can lead to both precocious and promiscuous sexual behavior. Many—or all—of these things may be true. The number of reasons not to have sex must be at least as high. Still, a handful of suspects came up again and again in my interviews and in the research I reviewed—and each has profound implications for our happiness. Sex for One The retreat from sex is not an exclusively American phenomenon. By 2012, the rate had dropped to fewer than five times. Over roughly the same period, Australians in relationships went from having sex about 1. In the Netherlands, the median age at which people first have intercourse rose from 17. This news was greeted not with universal relief, as in the United States, but with some concern. If people skip a crucial phase of development, one educator warned—a stage that includes not only flirting and kissing but dealing with heartbreak and disappointment—might they be unprepared for the challenges of adult life? The country, which has one of the highest birth rates in Europe, is apparently disinclined to risk its fecundity. In 2005, a third of Japanese single people ages 18 to 34 were virgins; by 2015, 43 percent of people in this age group were, and the share who said they did not intend to get married had risen too. Dismal employment prospects played an initial role in driving many men to solitary pursuits—but the culture has since moved to accommodate and even encourage those pursuits. It is also a global leader in the design of high-end sex dolls. What may be more telling, though, is the extent to which Japan is inventing modes of genital stimulation that no longer bother to evoke old-fashioned sex, by which I mean sex involving more than one person. He finds it cold and awkward, but understands its purpose. The vibrator figures in, too— found that just over half of adult women had used one, and by all indications it has only grown in popularity. Makes, models, and features have definitely proliferated. This shift is particularly striking when you consider that Western civilization has had a major hang-up about masturbation going back at least as far as Onan. Michael and his co-authors recount in Sex in America, J. Kellogg, the cereal maker, urged American parents of the late 19th century to take extreme measures to keep their children from indulging, including circumcision without anesthetic and application of carbolic acid to the clitoris. Thanks in part to his message, masturbation remained taboo well into the 20th century. Gary Wilson, an Oregon man who runs a website called , makes a similar claim. In , which features animal copulation as well as many human brain scans, Wilson argues that masturbating to internet porn is addictive, causes structural changes in the brain, and is producing an epidemic of erectile dysfunction. There is scant evidence of an epidemic of erectile dysfunction among young men. And no researcher I spoke with had seen compelling evidence that porn is addictive. Kerner believes this is why more and more of the women coming to his office in recent years report that they want sex more than their partners do. I n reporting this story, I spoke and corresponded with dozens of 20- and early-30-somethings in hopes of better understanding the sex recession. I talked with some who had never had a romantic or sexual relationship, and others who were wildly in love or had busy sex lives or both. Sex may be declining, but most people are still having it—even during an economic recession, most people are employed. The recession metaphor is imperfect, of course. I talked with plenty of people who were single and celibate by choice. Even so, I was amazed by how many 20-somethings were deeply unhappy with the sex-and-dating landscape; over and over, people asked me whether things had always been this hard. Despite the diversity of their stories, certain themes emerged. One recurring theme, predictably enough, was porn. Less expected, perhaps, was the extent to which many people saw their porn life and their sex life as entirely separate things. The wall between the two was not absolute; for one thing, many straight women told me that learning about sex from porn seemed to have given some men dismaying sexual habits. But by and large, the two things—partnered sex and solitary porn viewing—existed on separate planes. In first place, for the third year running, was lesbian a category beloved by men and women alike. The new runner-up, however, was hentai—anime, manga, and other animated porn. Porn has never been like real sex, of course, but hentai is not even of this world; unreality is the source of its appeal. Many of the younger people I talked with see porn as just one more digital activity—a way of relieving stress, a diversion. It is related to their sex life or lack thereof in much the same way social media and binge-watching TV are. Would I be having sex more? Even people in relationships told me that their digital life seemed to be vying with their sex life. Who would pick messing around online over actual messing around? An in the Journal of Population Economics examined the introduction of broadband internet access at the county-by-county level, and found that its arrival explained 7 to 13 percent of the teen-birth-rate decline from 1999 to 2007. Maybe adolescents are not the hormone-crazed maniacs we sometimes make them out to be. Maybe the human sex drive is more fragile than we thought, and more easily stalled. Hookup Culture and Helicopter Parents I started high school in 1992, around the time the teen pregnancy and birth rates hit their highest levels in decades, and the median age at which teenagers began having sex was approaching its modern low of 16. Women born in 1978, the year I was born, have a dubious honor: We were younger when we started having sex than any group since. Birth-control advocates naturally pointed to birth control. And yes, teenagers were getting better about using contraceptives, but not sufficiently better to single-handedly explain the change. Christian pro-abstinence groups and backers of abstinence-only education, which received a big funding boost from the 1996 welfare-reform act, also tried to take credit. Still, the trend continued: Each wave of teenagers had sex a little later, and the pregnancy rate kept inching down. In the past several years, however, a number of studies and books on hookup culture have begun to correct the record. One of the most thoughtful of these is American Hookup: The New Culture of Sex on Campus, by Lisa Wade, a sociology professor at Occidental College. Wade sorts the students she followed into three groups. The remainder were in long-term relationships. It also tracks with data from the Online College Social Life Survey, a survey of more than 20,000 college students that was conducted from 2005 to 2011, which found the median number of hookups over a four-year college career to be five—a third of which involved only kissing and touching. The majority of students surveyed said they wished they had more opportunities to find a long-term boyfriend or girlfriend. When I spoke with Wade recently, she told me that she found the sex decline among teens and 20-somethings completely unsurprising—young people, she said, have always been most likely to have sex in the context of a relationship. It turns out 1957 has the highest rate of teen births in American history. We have no social skills because we hook up. So what thwarted teen romance? Malcolm Harris strikes a similar note in his book, Kids These Days: Human Capital and the Making of Millennials. Addressing the desexing of the American teenager, he writes: A decline in unsupervised free time probably contributes a lot. At a basic level, sex at its best is unstructured play with friends, a category of experience that … time diaries … tell us has been decreasing for American adolescents. M , one of the most popular undergraduate classes at Northwestern University, was launched in 2001 by William M. Pinsof, a founding father of couples therapy, and Arthur Nielsen, a psychiatry professor. What if you could teach about love, sex, and marriage before people chose a partner, Pinsof and Nielsen wondered—before they developed bad habits? The class was meant to be a sort of preemptive strike against unhappy marriages. Under Alexandra Solomon, the psychology professor , it has become, secondarily,. She assigns students to ask someone else out on a date, for example, something many have never done. It may or may not have helped that a course with overlapping appeal, Human Sexuality, was discontinued some years back after its professor presided over a demonstration of something called a fucksaw. Over the course of numerous conversations, Solomon has come to various conclusions about hookup culture, or what might more accurately be described as lack-of-relationship culture. For one thing, she believes it is both a cause and an effect of social stunting. We have no social skills because we hook up. Most Marriage 101 students have had at least one romantic relationship over the course of their college career; the class naturally attracts relationship-oriented students, she points out. Nonetheless, she believes that many students have absorbed the idea that love is secondary to academic and professional success—or, at any rate, is best delayed until those other things have been secured. A classmate nodded emphatically. Another said that when she was in high school, her parents, who are both professionals with advanced degrees, had discouraged relationships on the grounds that they might diminish her focus. Even today, in graduate school, she was finding the attitude hard to shake. In early May, I returned to Northwestern to sit in on a Marriage 101 discussion section. Which is the topic of this week. The names of people who talked with me about their personal lives have been changed. That was a delight. But each time he went to one, he struck out. His friends set up a Tinder account for him; later, he signed up for Bumble, Match, OkCupid, and Coffee Meets Bagel. Unless you are exceptionally good-looking, the thing online dating may be best at is sucking up large amounts of time. He had better luck with Tinder than the other apps, but it was hardly efficient. He figures he swiped right—indicating that he was interested—up to 30 times for every woman who also swiped right on him, thereby triggering a match. But matching was only the beginning; then it was time to start messaging. This means that for every 300 women he swiped right on, he had a conversation with just one. In reality, unless you are exceptionally good-looking, the thing online dating may be best at is sucking up large amounts of time. As of 2014, , the average user logged in 11 times a day. Today, the company says it logs 1. He liked her, and was happy to be on hiatus from Tinder. Why not boycott them all? Simon said meeting someone offline seemed like less and less of an option. But the more people I talked with, the more I came to believe that he was simply describing an emerging cultural reality. As romance and its beginnings are segregated from the routines of daily life, there is less and less space for elevator flirtation. This shift seems to be accelerating amid the national reckoning with sexual assault and harassment, and a concomitant shifting of boundaries. Among older groups, much smaller percentages believe this. Laurie Mintz, who teaches a popular undergraduate class on the psychology of sexuality at the University of Florida, told me that the MeToo movement has made her students much more aware of issues surrounding consent. She has heard from many young men who are productively reexamining their past actions and working diligently to learn from the experiences of friends and partners. But others have described less healthy reactions, like avoiding romantic overtures for fear that they might be unwelcome. In my own conversations, men and women alike spoke of a new tentativeness and hesitancy. One woman who described herself as a passionate feminist said she felt empathy for the pressure that heterosexual dating puts on men. We worked on different floors of the same institution, and over the months that followed struck up many more conversations—in the elevator, in the break room, on the walk to the subway. And yet quite a few of them suggested that if a random guy started talking to them in an elevator, they would be weirded out. Another woman fantasized to me about what it would be like to have a man hit on her in a bookstore. But then she seemed to snap out of her reverie, and changed the subject to Sex and the City reruns and how hopelessly dated they seem. Video: The Sex Drought H ow could various dating apps be so inefficient at their ostensible purpose—hooking people up—and still be so popular? For one thing, lots of people appear to be using them as a diversion, with limited expectations of meeting up in person. The majority of men on Tinder just swipe right on everybody. They say yes, yes, yes to every woman. Online daters, he argued, might be tempted to keep going back for experiences with new people; commitment and marriage might suffer. Maybe choice overload applies a little differently than Slater imagined. This idea came up many times in my conversations with people who described sex and dating lives that had gone into a deep freeze. A nd yet online dating continues to attract users, in part because many people consider apps less stressful than the alternatives. The first time my husband and I met up outside work, neither of us was sure whether it was a date. I use dating apps because I want it to be clear that this is a date and we are sexually interested in one another. Dating apps have been a helpful crutch. Sexual minorities, for example, tend to use online dating services at much higher rates than do straight people. This disparity raises the possibility that the sex recession may be a mostly heterosexual phenomenon. The disparity was starker for women: About two-thirds of messages went to the one-third of women who were rated most physically attractive. A more recent study by researchers at the University of Michigan and the Santa Fe Institute found that online daters of both genders tend to pursue prospective mates who are on average 25 percent more desirable than they are—presumably not a winning strategy. The very existence of online dating makes it harder for anyone to make an overture in person without seeming inappropriate. So where does this leave us? Many online daters spend large amounts of time pursuing people who are out of their league. Few of their messages are returned, and even fewer lead to in-person contact. At best, the experience is apt to be bewildering Why are all these people swiping right on me, then failing to follow through? But it can also be undermining, even painful. Emma is, by her own description, fat. She is not ashamed of her appearance, and purposefully includes several full-body photos in her dating profiles. Nevertheless, men persist in swiping right on her profile only to taunt her—when I spoke with her, one guy had recently ended a text exchange by sending her a gif of an overweight woman on a treadmill. An even bigger problem may be the extent to which romantic pursuit is now being cordoned off into a predictable, prearranged online venue, the very existence of which makes it harder for anyone, even those not using the apps, to extend an overture in person without seeming inappropriate. What a miserable impasse. Bad Sex Painfully Bad One especially springlike morning in May, as Debby Herbenick and I walked her baby through a park in Bloomington, Indiana, she shared a bit of advice she sometimes offers students at Indiana University, where she is a leading sex researcher. These are all things that are just unlikely to go over well. Herbenick had asked whether we might be seeing, among other things, a retreat from coercive or otherwise unwanted sex. Just a few decades ago, after all, marital rape was still legal in many states. It retains its standing thanks partly to the productivity of its scientists, and partly to the paucity of sex research at other institutions. The previous national survey, out of the University of Chicago, was conducted just once, in 1992. She mentioned the new popularity of sex toys, and a surge in heterosexual anal sex. Back in 1992, the big University of Chicago survey reported that 20 percent of women in their late 20s had tried anal sex; in 2012, the NSSHB found a rate twice that. She also told me about new data suggesting that, compared with previous generations, young people today are more likely to engage in sexual behaviors prevalent in porn, like the ones she warns her students against springing on a partner. All of this might be scaring some people off, she thought, and contributing to the sex decline. Whether or not these rates represent an increase we have no basis for comparison , they are troublingly high. Studies show that, in the absence of high-quality sex education, teen boys look to porn for help understanding sex—anal sex and other acts women can find painful are ubiquitous in mainstream porn. Tess, a 31-year-old woman in San Francisco, mentioned that her past few sexual experiences had been with slightly younger men. If women are avoiding sex, are they trying to avoid the really bad sex? Masters and Virginia E. Johnson long ago posited was bad for sexual functioning. Research suggests that, for most people, casual sex tends to be less physically pleasurable than sex with a regular partner. For women, especially, this varies greatly. One study found that while hooking up with a new partner, only 31 percent of men and 11 percent of women reached orgasm. Other studies have returned similar results. If young people are delaying serious relationships until later in adulthood, more and more of them may be left without any knowledge of what good sex really feels like. As I was reporting this piece, quite a few people told me that they were taking a break from sex and dating. Some people told me of sexual and romantic dormancy triggered by assault or depression; others talked about the decision to abstain as if they were taking a sabbatical from an unfulfilling job. She was doubtful, though; he was in his 30s—old enough, she thought, to know better. Iris observed that her female friends, who were mostly single, were finding more and more value in their friendships. Several women also had a text chain going in which they exchanged nude photos of themselves. Which makes sense—the less time you spend naked, the less comfortable you are being naked. But people may also be newly worried about what they look like naked. A large and growing body of research reports that for both men and women, social-media use is correlated with body dissatisfaction. And a major Dutch study found that among men, frequency of pornography viewing was associated with concern about penis size. According to research by Debby Herbenick, how people feel about their genitals predicts sexual functioning—and somewhere between 20 and 25 percent of people, perhaps influenced by porn or plastic-surgery marketing, feel negatively. Conversely, not feeling comfortable in your own skin complicates sex. The 2017 iteration of Match. Ian Kerner, the New York sex therapist, told me that he works with a lot of men who would like to perform oral sex but are rebuffed by their partner. The term inhibition, for these purposes, means anything that interferes with or prevents arousal, ranging from poor self-image to distractedness. The first turns you on; the second turns you off. For many people, research suggests, the brakes are more sensitive than the accelerator. That turn-offs matter more than turn-ons may sound commonsensical, but in fact, this insight is at odds with most popular views of sexual problems. The other two factors come as no great shock either: Rates of anxiety and depression have been rising among Americans for decades now, and by some accounts have risen quite sharply of late among people in their teens and 20s. Anxiety suppresses desire for most people. From time to time she goes on dates with men she meets through her job in the book industry or on an app, but when things get physical, she panics. As we were ending the conversation, she mentioned to me a story by the British writer Helen Oyeyemi, which describes an author of romance novels who is secretly a virgin. I think about her all the time. Yet unhappiness inhibits desire, in the process denying people who are starved of joy one of its potential sources. Are rising rates of unhappiness contributing to the sex recession? Moreover, what research we have on sexually inactive adults suggests that, for those who desire a sex life, there may be such a thing as waiting too long. Among people who are sexually inexperienced at age 18, about 80 percent will become sexually active by the time they are 25. Over the course of a year, he reports, only 50 percent of heterosexual single women in their 20s go on any dates—and older women are even less likely to do so. Other sources of sexual inhibition speak distinctly to the way we live today. For women, getting an extra hour of sleep predicts a 14 percent greater likelihood of having sex the next day. One answer, which I heard from a few quarters, is that our sexual appetites are meant to be easily extinguished. Among the contradictions of our time is this: We live in unprecedented physical safety, and yet something about modern life, very recent modern life, has triggered in many of us autonomic responses associated with danger—anxiety, constant scanning of our surroundings, fitful sleep. Under these circumstances, survival trumps desire. But nobody ever died of not being able to get laid. Societal changes have a way of inspiring generational pessimism. And yet there are real causes for concern. One can quibble—if one cares to—about exactly why a particular toy retailer failed. At first, the drop was attributed to the Great Recession, and then to the possibility that Millennial women were delaying motherhood rather than forgoing it. But a more fundamental change may be under way. In 2017, the U. Birth rates are declining among women in their 30s—the age at which everyone supposed more Millennials would start families. As a result, some 500,000 fewer American babies were born in 2017 than in 2007, even though more women were of prime childbearing age. Over the same period, the number of children the average American woman is expected to have fell from 2. If this trend does not reverse, the long-term demographic and fiscal implications will be significant. A more immediate concern involves the political consequences of loneliness and alienation. See also the populist discontent roiling Europe, driven in part by adults who have so far failed to achieve the milestones of adulthood: In Italy, half of 25-to-34-year-olds now live with their parents. When I began working on this story, I expected that these big-picture issues might figure prominently within it. I also imagined, more hopefully, a fairly lengthy inquiry into the benefits of loosening social conventions, and of less couple-centric pathways to a happy life. But these expectations have mostly fallen to the side, and my concerns have become more basic. A fulfilling sex life is not necessary for a good life, of course, but lots of research confirms that it contributes to one. Having sex is associated not only with happiness, but with a slew of other health benefits. The relationship between sex and wellness, perhaps unsurprisingly, goes both ways: The better off you are, the better off your sex life is, and vice versa. Unfortunately, the converse is true as well. Not having a partner—sexual or romantic—can be both a cause and an effect of discontent. Moreover, as American social institutions have withered, having a life partner has become a stronger predictor than ever of well-being. Like economic recessions, the sex recession will probably play out in ways that are uneven and unfair. Those who have many things going for them already—looks, money, psychological resilience, strong social networks—continue to be well positioned to find love and have good sex and, if they so desire, become parents. But intimacy may grow more elusive to those who are on less steady footing. When, over the course of my reporting, people in their 20s shared with me their hopes and fears and inhibitions, I sometimes felt pangs of recognition. Just as often, though, I was taken aback by what seemed like heartbreaking changes in the way many people were relating—or not relating—to one another. I am not so very much older than the people I talked with for this story, and yet I frequently had the sense of being from a different time. Sex seems more fraught now. This problem has no single source; the world has changed in so many ways, so quickly. In time, maybe, we will rethink some things: The abysmal state of sex education, which was once a joke but is now, in the age of porn, a disgrace. The dysfunctional relationships so many of us have with our phones and social media, to the detriment of our relationships with humans. In October, as I was finishing this article, I spoke once more with April, the woman who took comfort in the short story about the romance novelist who was secretly a virgin. It was so much better than I thought it was going to be. And he broke up with me. Beforehand, I figured that was the worst thing that could happen. And then it happened. The worst thing happened.

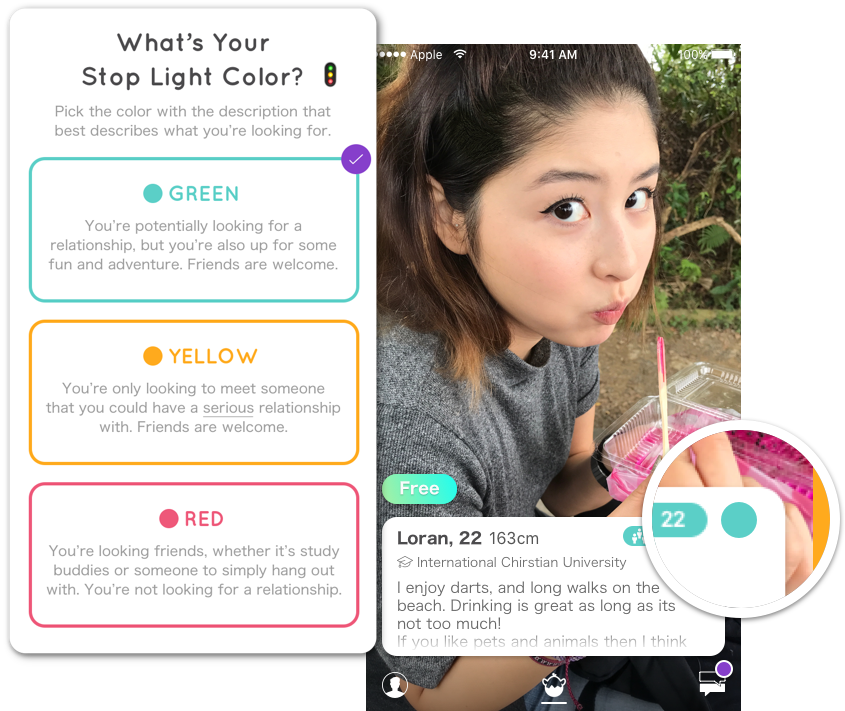

Addicted to Dating Apps

Encourage them to make new friends and build relationships at school, by participating in after-school sports and clubs, or by joining a religious group that offers clubs or meet-up groups designed specifically for teenagers. Malcolm Harris strikes a similar note in his book, Kids These Days: Human Capital and the Making of Millennials. Pinsof, a founding father of couples therapy, and Arthur Nielsen, a psychiatry professor. Many—or all—of these things dating apps young be true. What if you could teach about love, sex, and marriage before people chose a partner, Pinsof and Nielsen wondered—before they developed bad habits. The 2017 iteration of Match. Få en kæreste Going from dating to relationship Sikker chat på nettet

Views: 6

Comment

© 2025 Created by Diva's Unlimited Inc..

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of Divas Unlimited Inc to add comments!

Join Divas Unlimited Inc